A proposed class action lawsuit claims X Corp., which owns and operates Twitter, has wrongfully captured, stored and used Illinois residents’ biometric data, including facial scans, without consent. The suit more specifically alleges that Twitter has run afoul of the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act by capturing and storing users’ biometric information without notice or express consent and failing to provide policies that disclose how long it will retain their data and when it will be destroyed.

The filing contends that the company stores hashes of all images uploaded to the platform, thereby maintaining the digital scans of every person whose face appears in a photo without their consent.

Since 2015, Twitter has used software called PhotoDNA to “police” pornographic and other explicit images uploaded to the platform, the case explains. Per the complaint, the software works by creating a “hash,” or unique digital signature, of each uploaded image that is then analyzed against other hashes. The image is then tagged by Twitter if determined to be explicit.

Despite this, the defendant has failed to notify Twitter users that it captures and stores their biometric information and has not disclosed any data retention or destruction policies, as required by law, the case claims.

The lawsuit looks to represent any Illinois residents whose biometric data was collected, stored or used by Twitter by way of its use of software to analyze uploaded images containing their faces.

The Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA)

The Illinois BIPA, took effect in October 2008 is a state privacy law aimed at regulating the “collection, use, safeguarding, handling, storage, retention, and destruction” of Illinois residents’ biometric information. The statute covers biologically unique identifiers such as fingerprints, retina or iris scans, voiceprints, hand and face geometry, and any “biometric information” based on such identifiers.

Under the BIPA, no entity is permitted to obtain consumers’ biometric information without first: Informing them in writing that their information will be collected or stored; Informing them in writing of the purpose and length of time for which their information will be collected, stored, and used; and Receiving written consent from the individuals to collect and store their information.

In addition to these requirements, the entity collecting biometric information must also publish a publicly available retention schedule and guidelines detailing how and when the data will be destroyed.

Importantly, the statute grants Illinois consumers a private right of action, meaning they can sue any potential offender to collect no less than $1,000. If the court finds that the offender’s actions were intentional or reckless, the award increases to the greater of $5,000 or actual damages.

This brings us to our ever-increasing pool of class action lawsuits alleging violations of the BIPA. Perhaps the most notable cases filed under the statute, such as the Home Depot case we mentioned earlier, challenge businesses’ use of facial recognition software to collect scans of consumers’ faces.

The Home Depot BIPA Lawsuit

A “faceprint,” as explained in the Home Depot suit, is made up of various measurements of a person’s face geometry, such as the distance between the eyes, nose, and ears.  The data is collected by scanning photos or videos of a person’s face and compiling the data points into a string that can be stored and recognized.

The data is collected by scanning photos or videos of a person’s face and compiling the data points into a string that can be stored and recognized.

Faceprints, according to the Home Depot case, can be used with facial recognition software to identify certain individuals and track their activity. The complaint details the alleged process:

As the customer moves through a store and is detected by cameras, the facial-recognition technology repeatedly re-maps the customer’s facial geometry, and compares it against the stored faceprint, all while tracking the individual’s movement throughout the store.”

According to the case, this alleged practice is framed as a “loss-prevention measure” that allows the retailer to identify “suspicious” shoppers and “track their every movement.” However unsettling that measure may be, it’s still legal in Illinois—but only if Home Depot gets every shopper’s informed consent first and makes the required BIPA disclosures discussed above.

So, unless you remember signing paperwork before walking into an Illinois Home Depot, you may be owed up to $5,000, the lawsuit argues.

Home Depot isn’t the only business that has come under fire for its alleged face-scanning practices, though.

Other platforms have also been hit with proposed class action suits, as is the case for Snapchat, and Tinder who also collected and stored the facial scans of every person whose face appears in a photograph uploaded to the platforms, as part of the defendants effort to detect and filter explicit images.

Is This You?: Online Photo Scanning Lawsuits

Long before the Home Depot case was filed, Facebook was hit with several proposed class action lawsuits over its “tag suggestions” feature that reportedly uses facial recognition software to identify individuals in photos uploaded to the social media platform. The lawsuits allege that Facebook violated the Illinois BIPA by scanning each photo and compiling “face templates” to match with specific individuals, some of whom don’t even have a Facebook account and never provided consent for their biometric information to be collected and stored.

Similarly, personalized products company Shutterfly and video-streaming platform Vimeo have also been named in BIPA lawsuits over their apparent use of facial recognition software. The cases claim users have uploaded photos and videos to Shutterfly’s website and Magisto, Vimeo’s video-editing app, while remaining blissfully unaware that the companies were generating “highly detailed geometric maps” of the faces of individuals who appeared in the content.

What’s notable about these lawsuits is that they potentially affect millions of people, meaning they could come with an enormous price tag (up to $35 billion in Facebook’s case) if each person is awarded even the lowest statutory amount of $1,000 per violation. Facebook announced in September that its facial recognition feature would be turned off by default for all new users and all existing users who chose to do nothing in response to the company’s notification of the new feature. Ethical hacker John Opdenakker told Forbes the move was “yet another privacy related change driven by the fear of legal cases.”

Considering the number of BIPA cases that have been filed in recent years, it has been argued that companies who collect consumers’ biometric information should be worried.

BIPA Lawsuits: A Trend or a Warning?

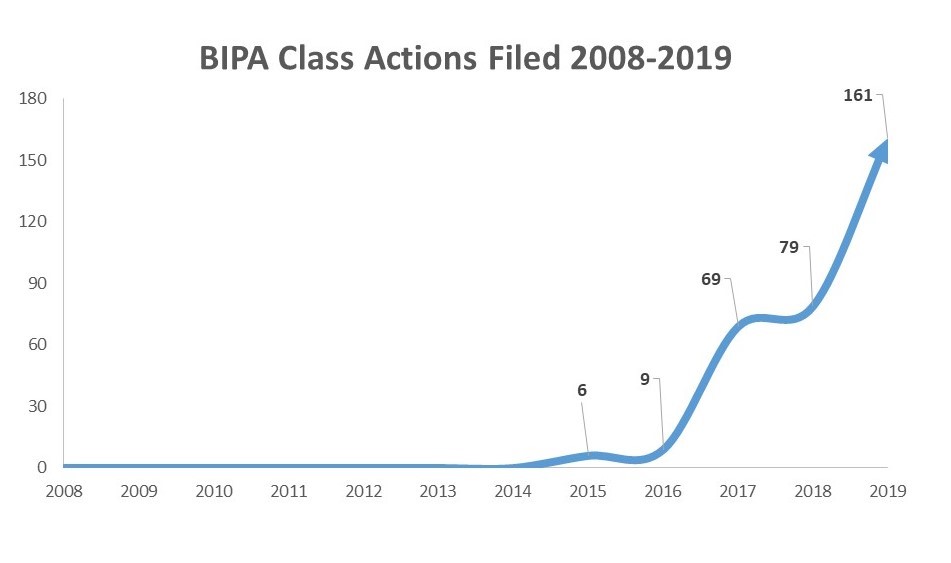

According to Seyfarth Shaw LLP, 324 class action lawsuits have been filed under the Illinois BIPA as of June 2019. (We’ve covered several of them on our site.)

Even though the BIPA was enacted back in 2008, no lawsuits were filed under the law until 2015, and the majority of the cases (309, to be exact) were filed between 2017 and June 2019.

For illustration, here’s a chart from Seyfarth Shaw’s blog:

The lawsuits have targeted any business that collects biometric information, from employers who use workers’ fingerprints to track their hours (such as Hilton Chicago, White Castle, and Crate & Barrel), to theme parks like Universal Orlando that scan visitors’ fingerprints each time they walk through the entrance gates.

Just last month, Apple was sued over the tech giant’s alleged practice of collecting users’ voiceprints when they activate Siri on an Apple device.

Whether the BIPA violations are intentional or not, the vast number of lawsuits has started a national conversation about data privacy concerns that could lead to positive changes for consumers, including more transparency about how their data is used, changes in companies’ policies, and even new legislation that aims to provide greater protection.

New Laws on the Horizon

Will Home Depot customers get a nice chunk of change just for browsing an Illinois store’s electric drill options? The answer to this question remains to be seen, as does the full effect of this flood of BIPA litigation. After all, most of the cases are still progressing through the court system, and anyone familiar with class actions knows they can often take years to reach resolution.

Yet even in their early stages, these lawsuits—and the law behind them—have paved the way for lawmakers in other states, including Delaware, Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, Oregon, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Rhode Island, to propose new legislation that aims to protect consumers’ biometric data.

Several state legislatures, such as those of Arkansas, California, Washington, and New York, have amended existing state privacy laws to include biometric data among protected personal information.

Notably, Massachusetts’ proposed bill, titled “An act relative to consumer data privacy,” calls for a private right of action that would allow consumers to sue for statutory damages of up to $750 per violation. So far, Illinois is the only state with a biometric privacy law that includes a private right of action. Current laws in Washington and Texas, and several of the proposed laws in other states, allow for only those states’ attorneys general to sue over potential violations. If passed, the Massachusetts law is set to go into effect in January 2023.

The Winding Road Ahead

Despite these positive steps toward stronger biometric data protection, the road to change is often a long (and winding) one. A proposed law that mirrored the Illinois BIPA was struck down in Florida this past May. And there’s even been some talk in the Illinois legislature about removing the private right of action included in the BIPA, instead granting enforcement authority to the Department of Labor and the Illinois Attorney General. Some speculate that this amendment could quell the tide of BIPA class actions and provide some much-needed clarity for employers who collect biometric information.

Whether the Illinois BIPA’s private right of action is the best solution to protect consumers’ biometric data is an argument for another day. The fact of the matter is that the law and its wake of class actions have brought national attention to a growing privacy issue that has begun to be addressed, though there’s still a lot of progress to be made.