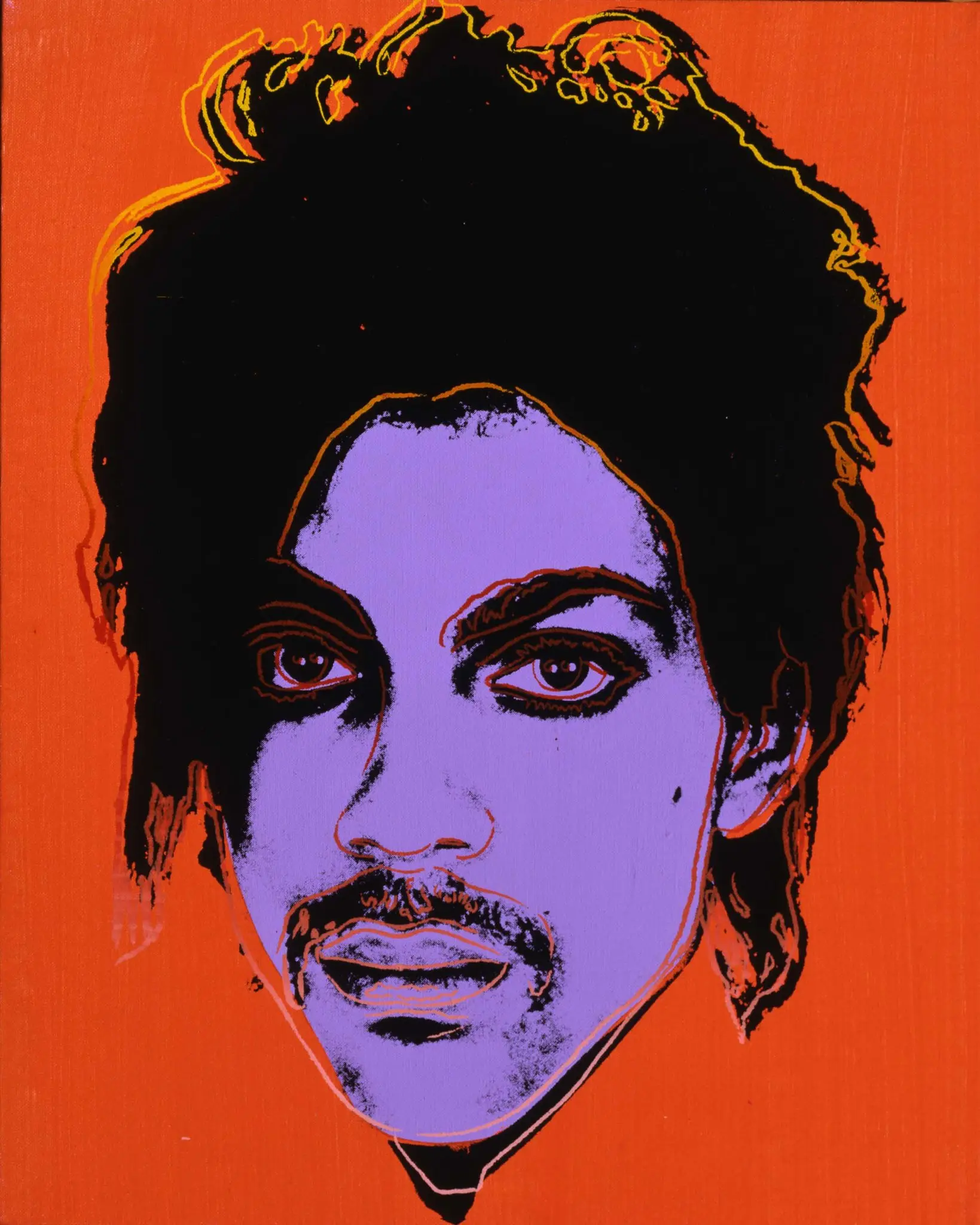

SCOTUS applied the fair use doctrine in a manner coherent with its previous rulings. The Orange Prince silkscreen licensed to Condé Nast constitutes copyright infringement, because a commercial license is not fair use.

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-869_87ad.pdf

To cite the court: the “purpose and character” of the Foundation’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph in commercially licensing Orange Prince to Condé Nast does not favor the fair use defense to copyright infringement.

Here are some first impression highlights:

Case History: The District Court considered the four fair use factors in 17 U. S. C. §107 and granted AWF summary judgment on its defense of fair use. The Court of Appeals reversed, finding that all four fair use factors favored Goldsmith. In this Court, the sole question presented is whether the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” §107(1), weighs in favor of AWF’s recent commercial licensing to Condé Nast.

(a) AWF contends that the Prince Series works are “transformative,” and that the first fair use factor thus weighs in AWF’s favor, because the works convey a different meaning or message than the photograph. But the first fair use factor instead focuses on whether an allegedly infringing use has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism.

- although new expression, meaning, or message may be relevant to whether a copying use has a sufficiently distinct purpose or character, it is not, without more, dispositive of the first factor.

- Here the specific use is AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast.

- AWF’s use of the photograph is of commercial nature.

- The commercial nature of a use is relevant, but not dispositive.

- Both the original photograph and AWF’s copying use of it are portraits of Prince depicting Prince in magazine stories about Prince, therefore both share the same purpose.

- “[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, . . . for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching . . . , scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” To determine whether a particular use is “fair,” the statute enumerates four factors to be considered. The factors “set forth general principles, the application of which requires judicial balancing, depending upon relevant circumstances.” Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 593 U. S. ___, ___.

- The first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or for nonprofit educational purposes, §107(1) considers the reasons for, and nature of, the copier’s use of an original work. The central question is whether the use “merely supersedes the objects of the original creation (supplanting the original), or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. 510. U.S. 569, 579

- As most copying has some further purpose and many secondary works add something new, the first factor asks “whether and to what extent” the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original.

- the larger the difference, the more likely the fist factor weighs in favor of fair use. A use that has a further purpose or different character is said to be transformative, but that too is a matter of degree.

- 21-869 Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (05/18/2023)

- In a broad sense, a use that has a distinct purpose is justified because it furthers the goal of copyright, namely, to promote the progress of science and the arts, without diminishing the incentive to create.

Here is my previous comment on this case.